[Originally published at Christ and Pop Culture.]

“Ellen, come look at this,” my husband, Todd, requested.

We were five days sailing into our first ocean passage from Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, to the Marquesas Islands of French Polynesia in 2000. We expected the 2,800-mile journey to take close to four weeks and possibly a full month of blue water sailing. I sleepily uncurled from the off-watch bunk of our Cal 34 sailboat, Mandolin. Todd presented me with a weather fax he had downloaded via our HAM radio to our laptop. It showed that a Tropical Depression had developed to the southeast in the Gulf of Tehuantepec, the birthplace of Pacific Ocean hurricanes. This weather system had the potential to kill us. It was heading our way.

We assessed our situation: the relative positions of sailboat and storm, the speed and direction of each, the most likely scenarios, and the worst-case scenario of us moving slow and the storm moving at its top speed of 25 knots directly for us. Using logic and reasoning, we calmly made our decision. The wind being fickle, we fired up our engine and set a southwesterly course to cross to the south of the northwesterly traveling storm. Then, feeling nauseous, I climbed back into the bunk and began to pray.

A few weeks previous, we were trying to decide whether or not to embark on this trip. We knew that we were late in having Mandolin ready for her first ocean passage. One seasonal hurricane had already developed and blown across our path. Instead of crossing to the South Pacific before hurricane season, as all the wise and ready sailors had, we would be attempting to dodge between hurricanes.

While still in Mexico, Todd said one day, “I did something strange.”

“Oh?” I prompted.

“Yeah—I prayed. To God.”

We had been married for almost four years, and I knew that Todd didn’t truly understand what it meant to be saved from the consequences of his sins by trusting in Jesus’ death and resurrection. However, at that point, following Jesus wasn’t central to my life either. Rather than being a blazing furnace, my faith was merely a pilot light.

“Well—what did you ask Him?” I asked.

“I asked whether or not we should sail across the Pacific this year,” Todd replied.

“And what did He answer?”

“I haven’t heard anything back.”

A few weeks later, we headed out with several contingency plans should a hurricane begin to form in the Gulf of Tehuantepec. One of those plans was that if we made it past the offshore Revillagigedo Islands without any storm development, then continuing south would be the best plan of action should a system begin. Mere hours after passing the Revillagigedos, Todd downloaded the weather fax that showed tropical depression development.

Twelve hours and two weather faxes after making our decision to continue south, we were fairly certain of being in the clear from getting walloped by a hurricane. But hurricanes don’t always follow their own rules. Almost two years previous, the experienced sailing crew on Fantome made all the right maneuvers to stay out of the way of a hurricane in the Caribbean. However, the hurricane “consistently defied all predictions.” (Booklist review) All 31 crewmembers perished when the hurricane destroyed the ship.

Aboard Mandolin with a maximum hull speed of 6 knots (~7 miles/hour), we knew outrunning the storm wouldn’t have been an option had it barreled down on us. Thankfully, the storm followed its predicted path. As it passed well behind us, it gave us good wind to sail our desired course. Two and one half weeks later, we made landfall in the Marquesas Islands after 23 days at sea.

In the village where we landed was a Catholic Church; we attended a service a day or two after arriving. I was raised Roman Catholic and had worshiped in a few different denominations in my 20s, but I had never heard such robust singing as we heard in this church. My pilot-light faith was beginning to be fanned into a brighter flame.

“There are three things that are too amazing for me,

four that I do not understand:

the way of an eagle in the sky,

the way of a snake on a rock,

the way of a ship on the high seas,

and the way of a man with a young woman.”

Proverbs 30:18–19 (NIV)

Ocean passages give me a sense of timelessness. The ocean swell lifts our small craft up and then down, cresting the top of a swell, then sinking into the trough. On top of a swell, the wind presses stronger against the sail; the vessel heels further over. In the trough, the wind abates a bit; the vessel slightly rights itself. On top, my view takes in the expanse of ocean; in the trough, my view is diminished. Up and down, heeling and righting, horizon increasing and dwindling, the swells pass under our keel and I could be anyone at any time of history. I could be a Polynesian reading the waves, clouds, and birds to find the next island group. I could be a Puritan fleeing religious persecution in Europe, turning my face toward the New World. I could be a trader seeking goods and profit. Each of these people experienced what I experience on the open ocean. The wind and water continue in the patterns the Creator set in motion; they are still doing what they have always done, and no mortal shall tame them.

One of my favorite ocean experiences occurred on our Mexico to Marquesas voyage, when we were sailing near the latitude of 11 degrees North. At these latitudes, one can see both the North Star and the Southern Cross in the night sky. We were able to see them at either side of the horizon for several nights. Into our portable CD player I put the only Crosby, Stills, and Nash CD we had with us and—listening over and over—taught myself all the words to “Southern Cross.” Sails flying, Mandolin cutting through the water nicely making way, stars majestically displayed above, and music to celebrate it all.

“The heavens declare the glory of God;

the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

Day after day they pour forth speech;

night after night they reveal knowledge.”

Psalm 19:1–2 (NIV)

Throughout our six months in the South Pacific islands, whenever we were anchored near a church on a Sunday, we would attend the service. Largely it was to enjoy the music of the islands. However, we were drawn by more than the music and singing. It possessed a vigor not experienced at island tourist shows. The people in the churches were not performing; they were worshiping. And even though we could not understand the words, the intensity and sincerity were evident.

Ocean sailing also gives one much time to think. We were living our dream—the same dream of many who never manage to attain it. We had worked years toward making this dream a reality, both at work to earn money and on our boat to physically ready her. Yet, while wonderful in many ways, the reality of our dream was turning out hollow. Surely there was more to life than merely the pursuit of leisure, recreation, and sight seeing? For surely sight seeing was really all this trip was… although it was an unusual, adventurous way to go about it.

“ ‘Meaningless! Meaningless!’

says the Teacher.

‘Utterly meaningless!

Everything is meaningless.’ ”

Ecclesiastes 1:2 (NIV)

We sailed and anchored throughout the Marquesas Islands, the Tuamotu Islands, and the Society Islands—they of Papeete, Moorea, and Bora Bora fame. We came upon the date of our fourth wedding anniversary while en route to the Cook Islands. We celebrated at 2 a.m. by fixing our broken self-steering wind vane, one of our most vital pieces of gear. In the Cook Islands, I realized that I was facing my 34th birthday soon. We had no children and had been fence-sitting on the decision, yea or nay. My eggs weren’t getting any younger.

Considering whether or not to try to have children brings up all sorts of questions on how to raise said theoretical children. At one point, Todd mentioned that if we possessed character traits that we did not want to pass on to children, we should change them. I responded that if we have character traits we do not like about ourselves, we should change them whether we ever had children or not. And I realized that a huge part of the development of who I am and what I believe is the result of my parents taking my siblings and me to church every Sunday. I knew that I would want to do the same for my own children. I knew I wanted to do the same for myself. And I began to pray in earnest the prayer I had haphazardly prayed throughout our four-year marriage: “Lord, please make our marriage a Christ-centered marriage. I don’t know what that looks like or how to attain it. Please bring my husband to faith in You and make our marriage Christ-centered. Amen.”

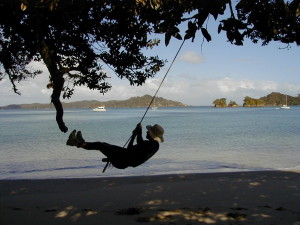

Within the Cook Island group, Palmerston Island atoll is accessible only by water as there is no air landing strip and it is too far from any other land for a helicopter to reach. Settled in 1863 by William Marsters and his four Polynesian wives, in the 1970s descendants reportedly numbered over 1,000. About 50 were living on the island when we traveled through. Palmerston was one of the few places where we saw palm frond structures. Our photo, used in this article, depicts one of these huts along with a white sand beach, blue lagoon, and several palm trees often elicits from viewers, “Oh, paradise!” We thought so too, at one time, but discovered that appearances are not reality.

It’s easy to romanticize such a place. Even the BBC has done it. Receiving only a few supply ships per year, sailing vessels are warmly welcomed as sailors bring food and supplies to give to the islanders. In the 1920s and ’30s, passing ships and yachts sometimes saved the inhabitants from extinction by starvation after the island was stripped of vegetation by a hurricane. The extended Marsters family maintains three distinct branches based on descent from three of William Marsters’ wives. When a sailboat approaches, members of each family race out to meet it in their small, open fishing skiffs. Whoever makes contact first, welcomes the sailing crew into their branch family for the duration of their stay.

Which is why we found two skiffs racing toward us upon our approach around the island’s southern reaches. I was at the helm while my husband was lying in the off-watch bunk wearing a neck brace. He had had a painful fall in the cockpit the night before, badly hurting his neck. One skiff came alongside, motored parallel to us, matched our speed of 5 knots, and then a large Polynesian man leaped from his skiff onto Mandolin. He and his relations in the skiff guided my steering into the anchorage and helped me secure the anchor in the poor holding ground.

So there I was at the most remote island and the least secure anchorage we expected to visit during our South Pacific travels, with my husband in a neck brace, not sure if he had a hairline fracture in his neck that was just waiting to paralyze him. A fellow sailor, who was also a medical doctor, was anchored nearby. He happened to be on the water in another skiff and stopped alongside Mandolin after the anchor was down. Learning of Todd’s injury, he climbed aboard and proceeded with an examination. Watching the doctor’s instinctive expertise as he had Todd move his head and back in distinct ways assured me that we would receive a proper diagnosis. And when that diagnosis came back that Todd did not have any kind of injury that could be inadvertently exacerbated, my relief was profound.

The Marsters men had waited patiently during this interaction, then ferried us through the shallow, twisting channel that was too narrow and shallow for Mandolin to navigate. They safely brought us into the lagoon and then to shore.

“Welcome home,” the matriarch of our new family greeted us.

For all their hospitality—and despite the paradisaical setting—the 50 people living on the island have a difficult time getting along with each other. One man had started a small business to sell items to sailors. Others were angry at this development since no cash business had ever existed on Palmerston. While walking through the village, we heard one man on the shortwave radio speaking with authorities on Rarotonga, the Cook Islands’ seat of government. He was complaining that another branch of the family was hogging use of the tractor. The church on Sunday was the least populated with the most anemic singing we experienced in all the South Pacific. Reading from the Bible out loud, a 19-year-old man had difficulty stringing together the words.

The universe’s state of entropy, its state of gradual decline into disorder, is also in evidence even here in “paradise.” One of the women was suffering from an abscessed tooth with only primitive medical treatment available to her. The devastation caused by hurricanes has already been mentioned. And we experienced a potentially life-altering injury while on our way there with the next nearest island and better medical facilities a four-day sail away. So, when people exclaim that Palmerston is paradise, we remind them that family—spouses, parents and children, brothers and sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles—are going to have conflict. And that sin, disease, injury, natural disaster, and death are found everywhere on this planet; Palmerston is no exception.

From the Cook Islands, we sailed through the island nation of Niue, then the Kingdom of Tonga, and finished with an unexpectedly speedy and comfortable eight-day passage to New Zealand. This notorious stretch of water has claimed many vessels and lives. Such was the case in 1994 during The Queen’s Birthday Storm. More sailors’ lives were lost in 1999. However, rather than the discomfort and potential damage we had braced for, we enjoyed a brisk, exhilarating passage.

“Some went out on the sea in ships;

they were merchants on the mighty waters.

They saw the works of the Lord,

his wonderful deeds in the deep.

For he spoke and stirred up a tempest

that lifted high the waves.

They mounted up to the heavens and went down to the depths;

in their peril their courage melted away.

They reeled and staggered like drunkards;

they were at their wits’ end.

Then they cried out to the Lord in their trouble,

and he brought them out of their distress.

He stilled the storm to a whisper;

the waves of the sea were hushed.

They were glad when it grew calm,

and he guided them to their desired haven.

Let them give thanks to the Lord for his unfailing love

and his wonderful deeds for mankind.

Let them exalt him in the assembly of the people

and praise him in the council of the elders.”

Psalm 107:23–32 (NIV)

During our journey across the Pacific and through the islands, the majesty of God’s creation awed and humbled us. The brokenness and brutality of that same creation terrified us. And the hollowness of life lived for one’s own pursuits and pleasures became evident to us. Approaching the Marquesas toward the end of our first passage, I didn’t know how I would react when we finally sighted land. After waking at dawn, I joined Todd in the cockpit to see a mountain silhouette rising out of the water. We hooted, hollered, jumped up and down, laughed, and hugged each other. En route to New Zealand, it had been six months since embarking from Mexico. We had experienced stormy seas and tranquil waters, awe-inspiring beauty augmented by mortal music and petty human grievances tearing communities apart, the thrill of new discoveries and the apparent meaninglessness of existence. We had survived a season of ocean passage making with all its incumbent perils and as well as its remarkable beauties. I was on watch while Todd slept down below in the early morning hours when the thick, puffy cloud bank all across the horizon allowed me to see a jagged promontory extending out into the ocean. The Maori name, Aoteoroa, was living up to itself: Land of the Long White Cloud. Land. New Zealand. Tears pricked my eyes and trailed down my cheeks while a sense of accomplishment burned in my belly. LAND HO!

Along with that burn of accomplishment was the growing fire of a spiritual reawakening. A longing for something beyond what we had desired and expected convinced us that there must to be more to life and living than what one could experience with one’s five senses. What had begun as a sight-seeing trip, God had turned into a spiritual journey. By the time we were in New Zealand, my faith in Creator God and His justice and mercy displayed to us through Jesus Christ was ablaze within me.

“The church services are now in English,” I said to Todd. “We’ll be able to understand what they’re saying.” He was content to follow along, but his enthusiasm did not match mine. In various services, the crystal clear Gospel message was presented to us time and time again. At least, it was clear to me.

“What did you think?” I asked Todd after one such service.

“I just don’t understand this whole resurrection thing,” he responded. To Todd, it was clear as mud.

But within six months, Todd did understand—and choose to put his faith and trust in Jesus. His faith journey had started coming to a head at a church dinner in Whangarei, New Zealand. Sitting across from each other, Todd looked down at his paper place mat. All around the edge were quotes. Todd looked at me and remarked, “Do you remember the weird thing I did when we were trying to decide whether or not to embark—that I prayed?” I nodded. Todd turned his place mat around and pointed to the quote at the bottom center:

“If you wish to teach a man to pray, send him to sea.”